Der Tod des Heiligen Joseph. Variationen eines Themas.

Die apokryphe Historie des frommen Todes des Heiligen Josephs ist im Westen erst seit der Überlieferung des Mailänder Dominikaners Isidoro Isolano 1522 bekannt.[1] Der Tod des Joseph wird zum Vorbild des Sterbens nach einem langen, arbeitssamen und tüchtigen Leben stilisiert. Bald werden Bruderschaften des Hl. Joseph gegründet (zuerst 1557 in Bologna), deren Zweck es war den Sterbenden beizustehen. Eigenständigkeit in Form von Altarbildern hat die Szene erst Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts erlangt.[2] Erste Werke entstehen sehr früh und im Zusammenhang mit Marien- und Josephszyklen (umstritten in Augsburg und Bischofshofen, sowie in Brüssel oder San Martino Alfieri) und als Pendants zur Darstellung der Vermählung Mariens im Norden Italiens (Udine). Große Altarbilder des Themas sind kaum auf Hauptaltären zu finden (Ausnahmen sind u.a. Pollenza oder Kollerschlag), sondern an Nebenaltären oder in Seitenkapellen, die zumeist eben jene Bruderschaften stifteten.[3] Allgemein lässt sich festhalten, dass die Verehrung des Josephtodes eine „Zeit schöner Tode“ einleitete und allmählich den Erzengel Michael als Richter des Jüngsten Gerichts verdrängen sollte.[4]

Der tridentinische Fokus auf die Figur Mariens hebt die Bedeutung der Heiligen Familie. Die trianguläre Beziehungskonstellation der Heiligen Familie und die ohnehin zweifelhafte Verortung der Figur des Joseph darin forderten eine Erklärung und Fortsetzung der Erzählung heraus.[5] In den Evangelien tritt Joseph als Nährvater des Jesuskindes auf, doch verwindet nach der Kindheitsgeschichte. Was geschah mit ihm?

Zahlreiche Erbauungstexte und Schriften zum „guten Tod“ werden seit dem 16. Jahrhundert verbreitet.[6] Apokryph, nach koptischer Tradition, wird die Darlegung des Josephtodes als retrospektive Erzählung Christi an seine Jünger überliefert. Anhand dieser Erzählung ließen sich zumindest sechs konkrete Momente darstellen: 1.) Joseph ist krank im Bett, Jesus tritt herein, Joseph spricht letzte Worte; 2.) Jesus sitzt am Bett, hält die Hand und streichelt Joseph, Maria sitzt bei seinen Füßen; 3.) Joseph gibt Jesus ein Zeichen und stirbt, die Erzengel Michael und Gabriel kommen herbei; 4.) Besuch von Verwandten und Freunden; 5.) weitere Engel kommen herbei, Befehl Christi an zwei Engeln Joseph zu bekleiden; 6.) Segnung des toten Körpers durch Christus.

Gemeinsam mit Maria, die als passive Beisitzerin fungiert, ergab sich für die Künstler hiermit die einzige Möglichkeit der Darstellung der Heiligen Familie mit einem erwachsenen Jesus. Zum einen wird die Erzählung als intime Szene, zum anderen als Szene der Aktivität Christi als Befehlsgeber wie Segensspender umsetzbar. Im Zentrum steht die Beziehung zwischen Jesus Christus und Joseph. Der Sohn tritt in zwei Rollen auf: in der intimen Auslegung (tipo intimo) als Sohn Josephs (Jesus), wie in der aktiven Auslegung (tipo attivo) als Sohn Gottes (Christus). Stark unterschiedliche Zustände des Joseph bestimmen den ausgewählten Moment: bereits tot, sterbend, aber auch im Todeskampf, welcher dem „guten Tod“ eine Komponente der Passion verleiht und so die compassio im Betrachter verstärkt. Auch das sichtbare Alter des Sterbenden divergiert in den Darstellungen stark. Traditionell als sehr alter Mann gezeigt, weist die spanische und lateinamerikanische Tradition den Sterbenden oft sehr jung – als zweiten Jesus aus.

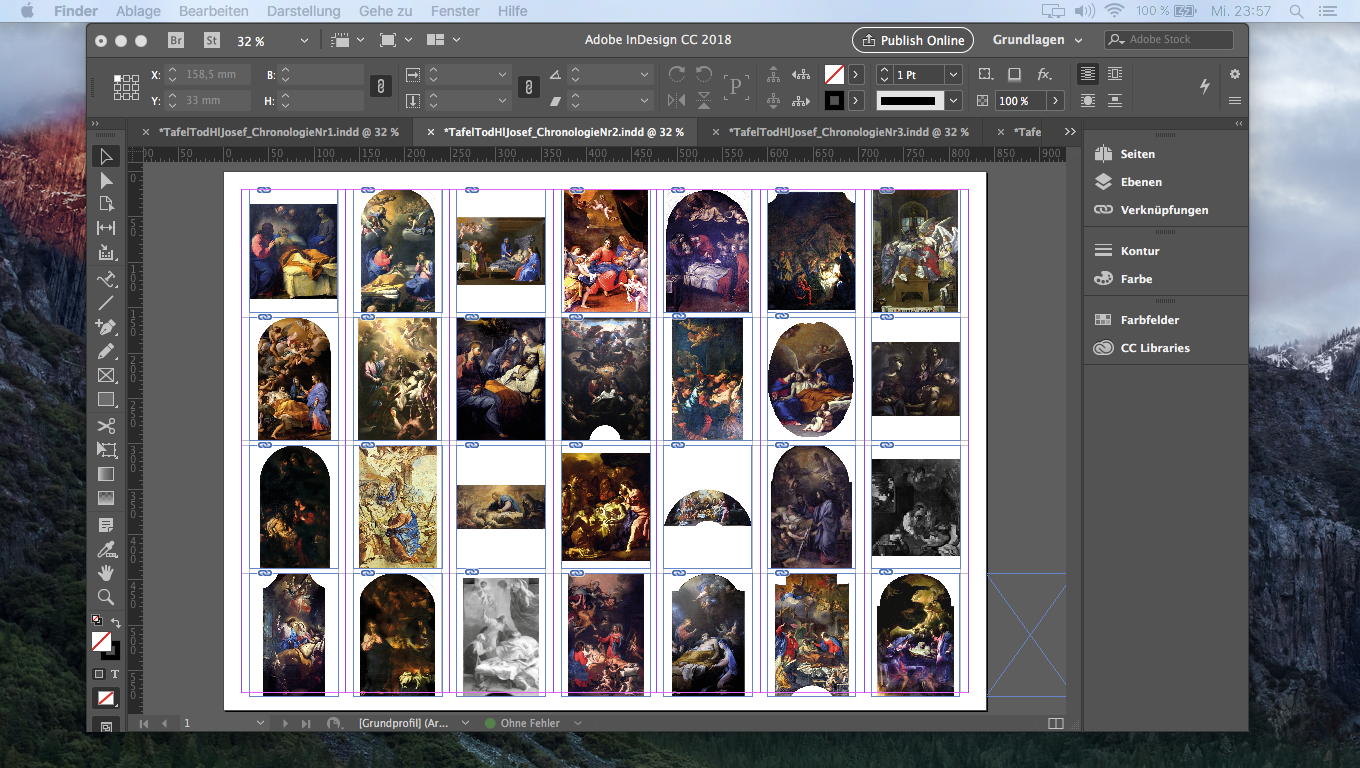

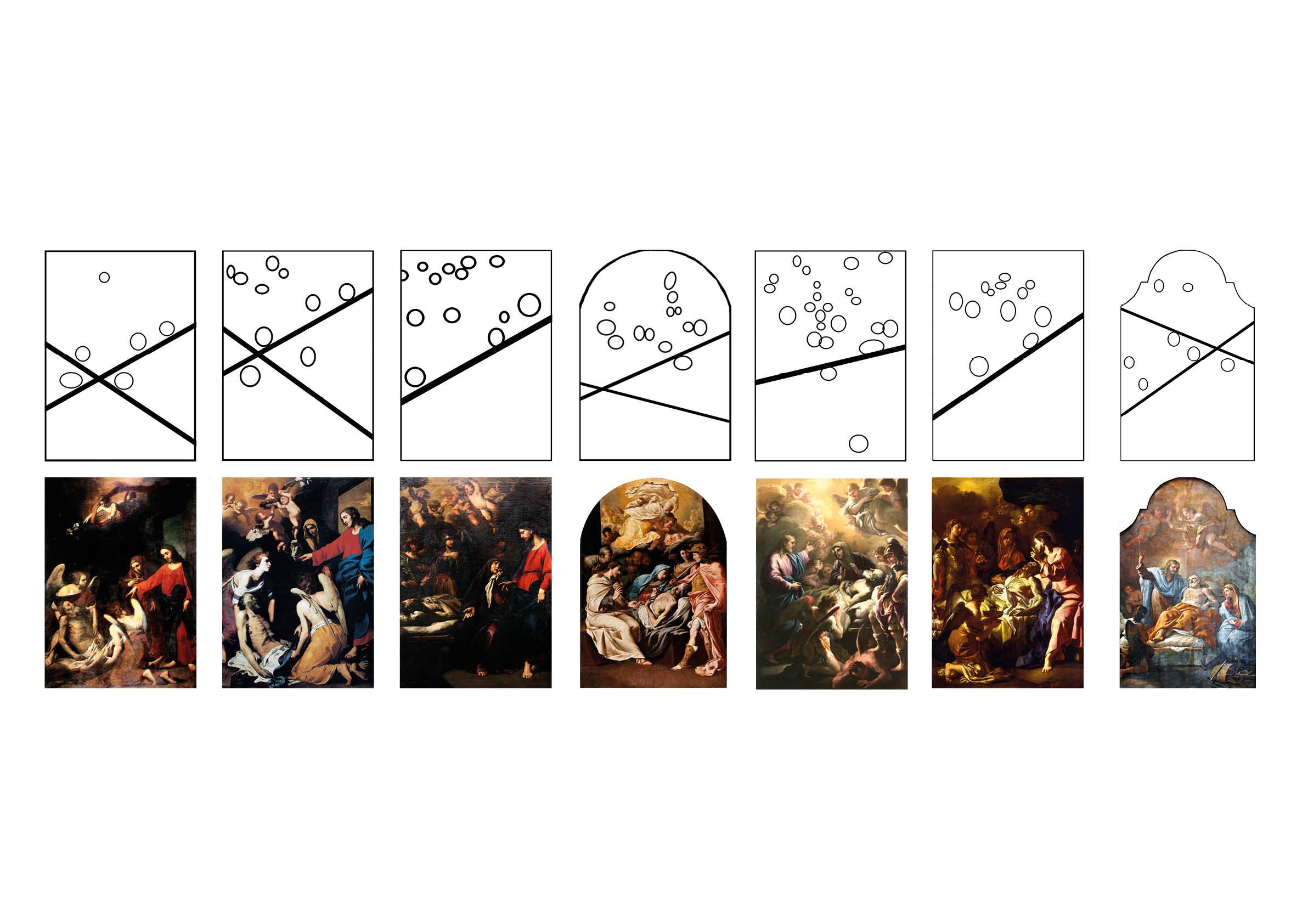

Das Projekt befindet sich seit ca. 2016 in Bearbeitung und ist noch nicht abgeschlossen. Neben einer allgemeinen Studie, werden regionale Entwicklungen einzeln behandelt (siehe Abbildung oben). Zentrum der Arbeit ist ein chronologischer Werkkatalog, worin über fünfhundert Werke bis zum Jahr 1806 behandelt werden.

…

Die Abbildung oben zeigt eine Analyse der Figurenkonstellation der Neapolitanische Tradition, von links nach rechts: Massimo Stanzione, Neapel, San Diego all‘Ospedaletto, Cappella Sabia, 1640; Francesco Guarino, Già a San Sossio di Serino, Corpo di Christo, 1642-45; Andrea Vaccaro, Neapel, Santa Maria delle Anime de Purgatorio ad Arco, 1650/51; Francesco Fracanzano, Neapel, Chiesa della Trinità dei Pellegrini, 1652; Luca Giordano, Ascoli Piceno, Pinacoteca Civica, 1677; Francesco Solimena, Salt Lake City, Utah Museum of Fine Arts, 1698-1700; Paolo De Matteis, Neapel, Crocelle (Chiesa della Concezione), 1726.

…

Die Abbildung der Titelseite: Andrea Vaccaro, Neapel, Museo Capodimonte, 1640-45.

…

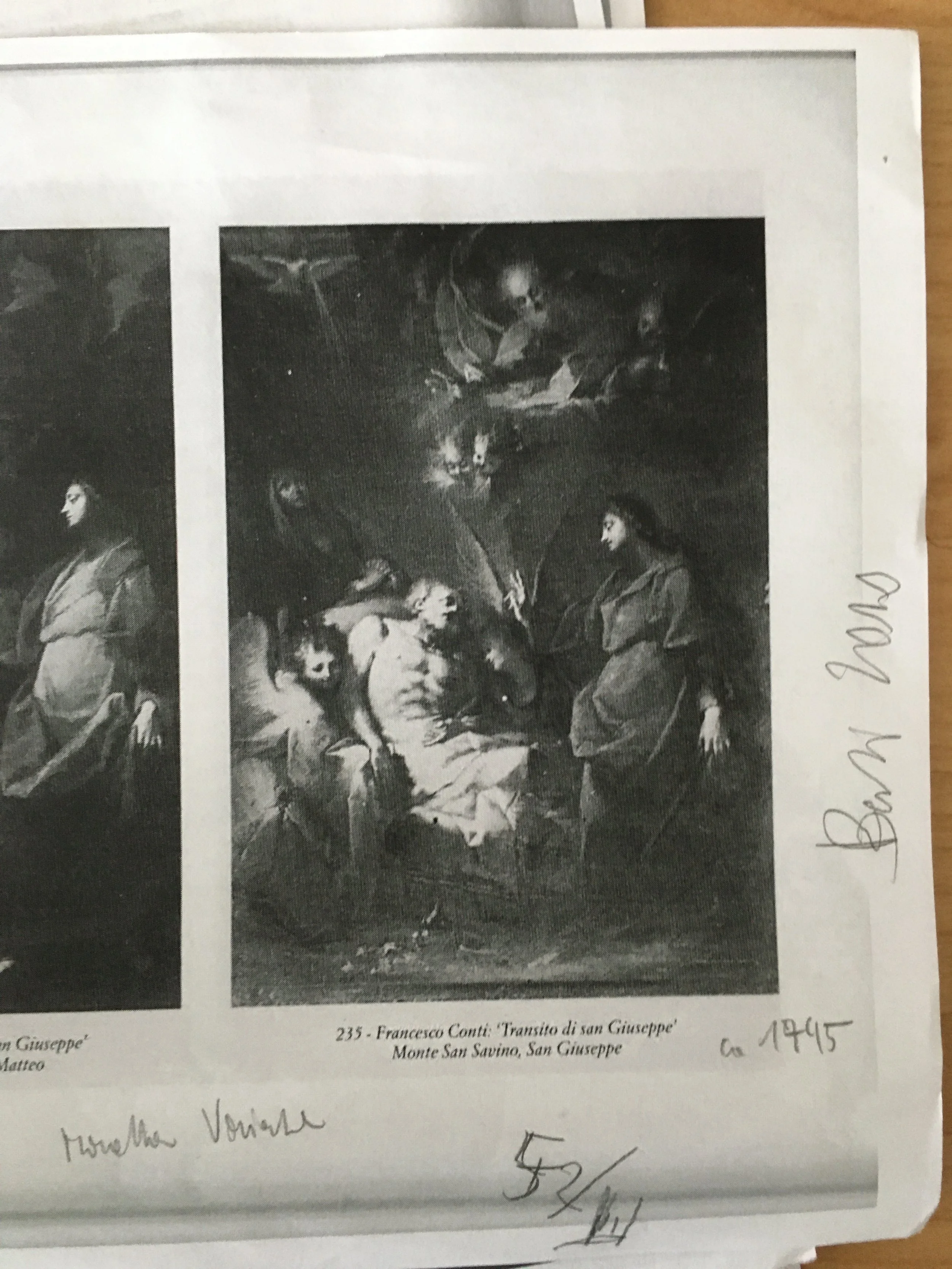

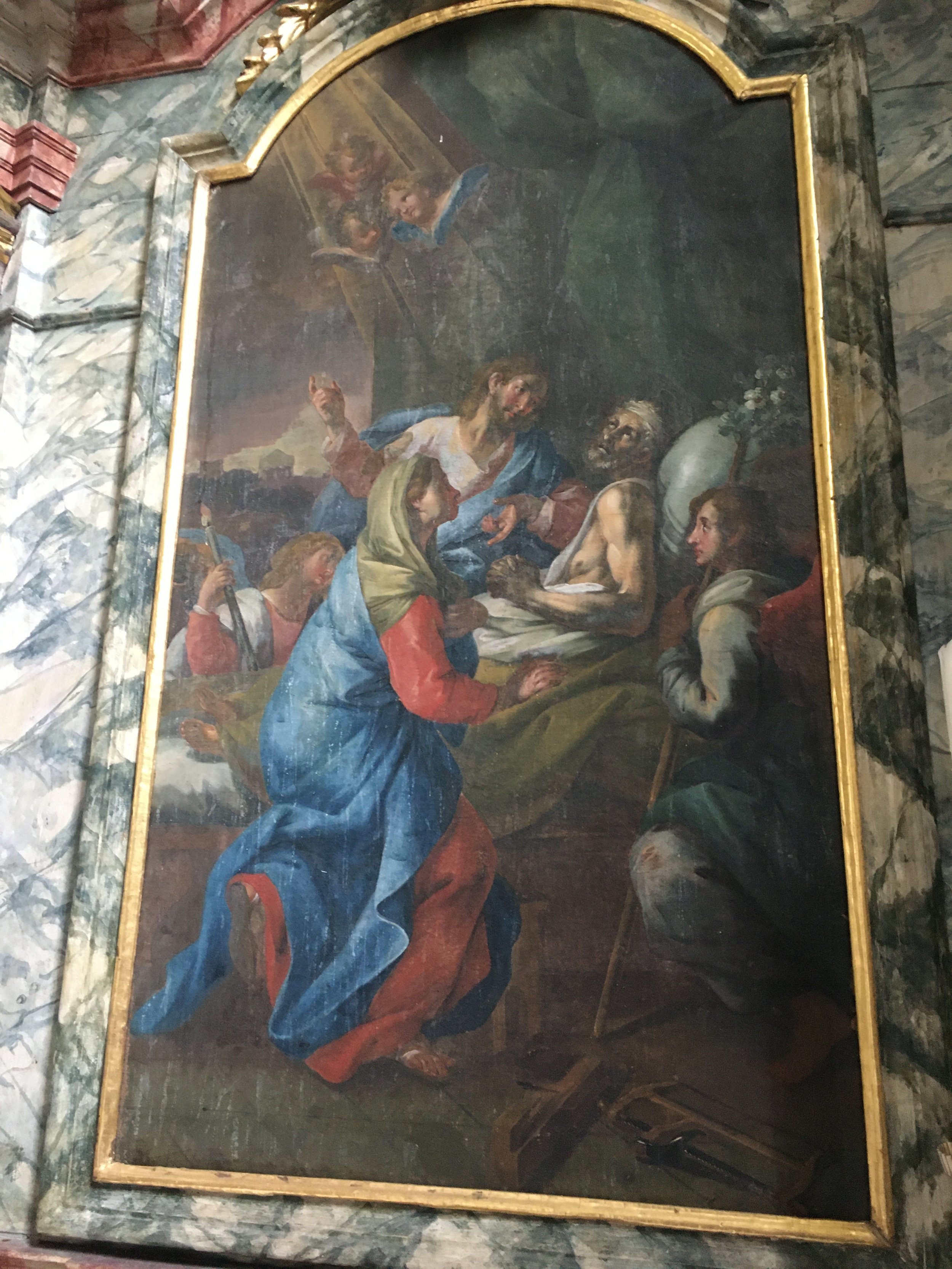

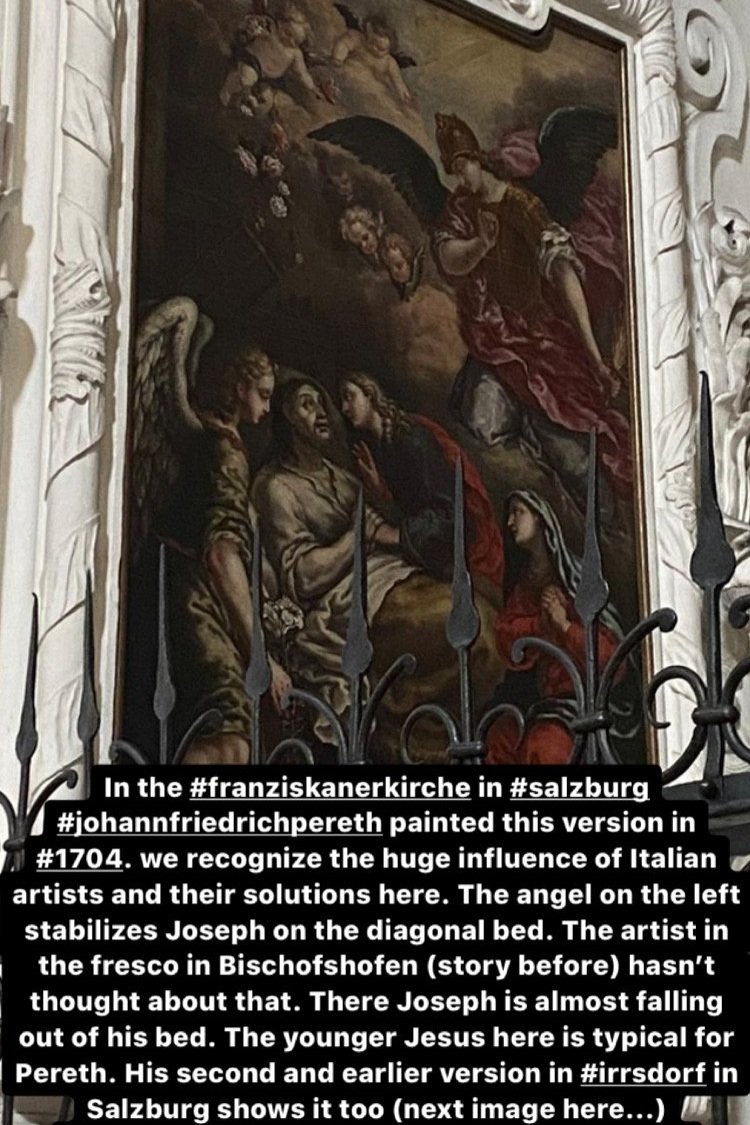

Die unten folgenden Abbildungen der Slideshow zeigen Einblicke in den Arbeitsprozess (Zusammenstellungen, Listen, Formalanalysen, Recherchen, Dokumentationen, usw.), 2020-23.

Für laufende Informationen über den Prozess der Recherchen und Berichte: Instagram Transito di San Giuseppe

[1] „Summa de donis sancti Joseph“, Pavia 1522.

[2] Zur Veranschaulichung der Tradition: Pigler 1974, S. 439-445.

[3] Die wenige Literatur, die es zu diesem Thema gibt, umfasst zumeist kurze Abhandlungen lokaler Traditionen. Genannt seien hier zu Rom: Garms 2002, zu Florenz: Berti, zu Genua und Ligurien: Montagni 1987 sowie Bocchini 1991 und zu Mexiko: Merlo Solorio 2013.

[4] Aries 1991, S. 135.

[5] Vgl. Koschorke 2000.

[6] Größtenteils erhalten diese Schriften keine Darstellungen. Gewisse Typen werden dennoch seit ca. 1610 in druckgrafischer Form verbreitet.

(English version below)

English version: The Death of Saint Joseph. Variations on a Theme.

The apocryphal story of the pious death of Saint Joseph has only been known in the West since the tradition of the Milanese Dominican Isidoro Isolano in 1522.[1] The death of Joseph was stylised as a model of dying after a long, hard-working and capable life. Soon confraternities of Saint Joseph were founded (first in Bologna in 1557) whose purpose was to assist the dying. The scene did not attain independence in the form of altarpieces until the beginning of the 17th century.[2] The first works appeared very early and in connection with cycles of Mary and Joseph (controversial in Augsburg and Bischofshofen, as well as in Brussels or San Martino Alfieri) and as counterparts to the depiction of the Marriage of Mary in northern Italy (Udine). Large altarpieces of the theme are rarely found on main altars (exceptions include Pollenza or Kollerschlag), but on side altars or in side chapels, most of which were donated by these same brotherhoods.[3] In general, it can be said that the veneration of the death of Joseph ushered in a "time of beautiful deaths" and gradually supplanted the archangel Michael as the judge of the Last Judgement.[4] The focus of the Tridentine focus on the death of Joseph was on the death of the Virgin Mary.

The Tridentine focus on the figure of Mary elevates the importance of the Holy Family. The triangular constellation of relationships in the Holy Family and the already dubious location of the figure of Joseph within it challenged an explanation and continuation of the narrative.[5] In the Gospels, Joseph appears as the foster-father of the infant Jesus but becomes obscure after the infancy narrative. What happened to him?

Numerous edification texts and writings on the "good death" have been circulated since the 16th century.[6] Apocryphally, according to Coptic tradition, the account of Joseph's death is handed down as a retrospective narrative of Christ to his disciples. Based on this narrative, at least six concrete moments could be depicted: 1.) Joseph is sick in bed, Jesus enters, Joseph speaks last words; 2.) Jesus sits at the bedside, holds Joseph's hand and caresses him, Mary sits at his feet; 3.) Joseph gives Jesus a sign and dies, the archangels Michael and Gabriel approach; 4.) visitation by relatives and friends; 5.) further angels approach, Christ's command to two angels to clothe Joseph; 6.) blessing of the dead body by Christ.

Together with Mary, who acts as a passive bystander, this provided the artists with the only possibility of depicting the Holy Family with an adult Jesus. On the one hand, the narrative becomes realisable as an intimate scene, on the other hand as a scene of Christ's activity as a command-giver (as well as a blessing-giver). Most important is the relationship between Jesus Christ and Joseph. The son appears in two roles: in the intimate interpretation (tipo intimo) as the son of Joseph (Jesus), as in the active interpretation (tipo attivo) as the Son of God (Christ). Strongly different states of Joseph determine the chosen moment: already dead, dying, but also in the throes of death, which gives the "good death" a component of passion and thus reinforces the compassion in the viewer. The visible age of the dying man also diverges greatly in the depictions. Traditionally shown as a very old man, the Spanish and Latin American tradition often shows the dying man as very young - as the second Jesus.

The project has been in progress since around 2016 and has not yet been completed. In addition to a general study, regional developments are dealt with individually (see figure above). The centre of the work is a chronological catalogue of works, in which over five hundred works up to the year 1806 are treated.

...

The figure above shows an analysis of the constellation of figures in the Neapolitan tradition, from left to right: Massimo Stanzione, Naples, San Diego all'Ospedaletto, Cappella Sabia, 1640; Francesco Guarino, Già a San Sossio di Serino, Corpo di Christo, 1642-45; Andrea Vaccaro, Naples, Santa Maria delle Anime de Purgatorio ad Arco, 1650/51; Francesco Fracanzano, Naples, Chiesa della Trinità dei Pellegrini, 1652; Luca Giordano, Ascoli Piceno, Pinacoteca Civica, 1677; Francesco Solimena, Salt Lake City, Utah Museum of Fine Arts, 1698-1700; Paolo De Matteis, Naples, Crocelle (Chiesa della Concezione), 1726.

...

Cover illustration: Andrea Vaccaro, Naples, Museo Capodimonte, 1640-45.

...

The slideshow images show glimpses of the working process (compilations, lists, formal analyses, research, documentation, etc.), 2020-23.

For further information of the process of research follow Instagram Transito di San Giuseppe

[1] "Summa de donis sancti Joseph", Pavia 1522.

[2] For an illustration of the tradition: Pigler 1974, pp. 439-445.

[3] The little literature that exists on this subject consists mostly of short treatises on local traditions. For Rome: Garms 2002, for Florence: Berti, for Genoa and Liguria: Montagni 1987 and Bocchini 1991, and in Mexico: Merlo Solorio 2013.

[4] Aries 1991, p. 135.

[5] Cf. Koschorke 2000.

[6] For the most part, these writings do not receive any representations. Certain types were nevertheless disseminated in printed form from around 1610 onwards.